Our car finished 2nd in the 1933 Mille Miglia and competed at Le Mans in 1938. It keeps its original engine, body, chassis and transmission, an extraordinary rarity for this model.

THESE CARS

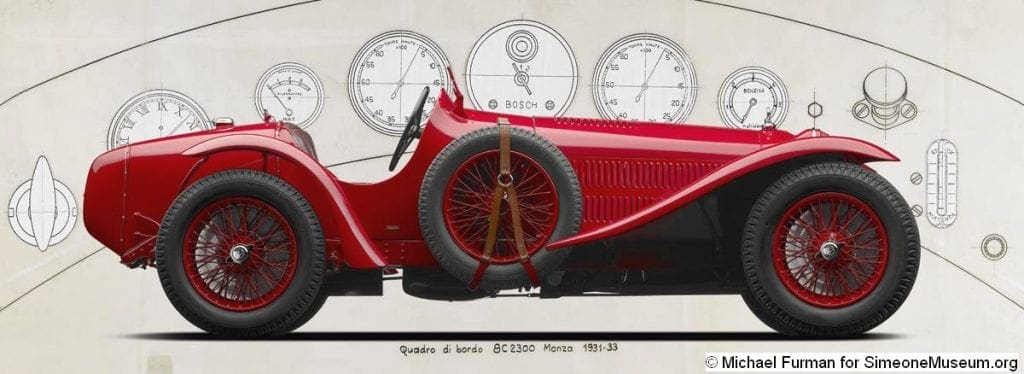

At the beginning of the 1930s, Alfa Romeo produced its first series- made super sports racing car, the 8C 2300. The supercharged double overhead cam engine soon became a world beater. Alfa produced them in three forms; the Le Mans, the longer chassis version with the obligatory rear seat (which won that great race in 1931, 1932, 1933, 1934 and almost in 1935); the short chassis Mille Miglia Spider (repeated road race champion of contests throughout Europe); and the Grand Prix Monza, (dominant in open wheeled racing throughout the first half of the 1930s.)

Although the exact number on Monzas made is unclear, it is fewer than the number of so-called Monzas which exist. We know, however, from factory records, the factory made that few Monza chassis. The vast majority of these 8C 2300 Grand Prix cars were the product of the Scuderia Ferrari racing organization, often converted from two passenger spiders. There are specific details which make up the Monza, mainly chassis changes, specific racing wheels and certain mechanical modifications which evolved over its racing career.

At the start of the 1930 racing season the Alfa Romeo factory precipitously withdrew. Their financial position made racing incongruous as absorption into a state-owned conglomerate started a turmoil. This included administrative confiscation of the works race cars which had been remarkably successful until then. This did not mean that they would stop making Monza race cars for others to enjoy. Their banner was taken up by the Scuderia Ferrari who seemed to find the resources to launch an extensive racing campaign throughout Europe and beyond. The customers for the new Monza’s included the names such as Caracciola, Chiron, Sommer, Wimille, Nasturzio and Castelbarco.

The entire history of the Monza Alfa Romeo is legendary and its entries and successes are too many to mention. I would refer you to Simon Moore’s epic three volume The Legendary 2.3, for a detailed car-by-car history of all the Monza’s both factory and those produced by the Scuderia Ferrari.

However, in both the sports car arena (when Monzas were equipped with fenders, lights, and a spare tire), and their more common Grand Prix configuration, they were essentially the state-of-the-art being challenged by the Bugatti Type 51, and larger displacement Maserati Grand Prix cars. Their tractability, reliability, and endurance usually led them past these formidable competitors.

OUR CAR

For the 1933 Mille Miglia, dillentante Count Carlo Castellbarco needed a winning car. He ordered from Alfa Romeo a full Monza chassis and had the body changed by Zagato who added beautiful flowing front and rear fenders, a spare, and headlights, to the magnificent Grand Prix car Alfa provided for him. With Franco Cortese, he was a contender in this race, and his most serious competition was, in fact, other 8C 2300 Alfa’s.

Cortese was excited to see the car which in typical fashion was completed the day before the race. I must recount literatim the oft-repeated comments of Count Giovanni Lurani in his exciting book Racing Round the World as follows, “Franco Cortese had carefully prepared, together with Castellbarco, the very new Monza 8-cylinder Alfa Romeo which would certainly be the fastest in the race. And one can imagine what a terrible shock it was for him, on arriving at the works early on Sunday morning (the morning of the race) to find the car abandoned, almost unrecognizable, in a corner of the garage; with a tail, tires and seats completely burnt out, the piping melted, and the electrical fittings destroyed! What happened was that around 7:00 the previous evening, when the car was still in the Works after the final test, the mechanic set about filling the tank but failed to notice that an electrician was still working under the car and the spark set fire to some spilt fuel and the car burst into flames. Bonini, the tester and Caracciola’s mechanic was seriously burned and the car was reduced to a pitiable state and pushed to one side as it was reckoned that it could be used no longer. It was in this state that Cortese found it just four hours before the start of the Mille Miglia but he could not lose heart. He immediately telephoned Castellbarco and shouted and stormed so much that he mobilized the entire personnel at the works. The workmen were able to take parts from other Monzas, reinstall electrical fittings, wheels, and tires and remarkably the car was ready to race. By then it was just an hour before the start of the race and everything seemed to be set, when the last piece of luck nearly spoiled everything. While filling the petrol tank a mechanic inadvertently poured in a can of water. There was nothing to do but to dismount the tank again, clean it carefully and remount it! All this was while precious minutes slipped by and it seemed impossible for them to start the race.”

In fact Cortese and Castellbarco sped down the autostrada averaging 200 kilometers per hour and “while the time keepers were calling them to line up they managed to leave with only a few seconds delay on their time.” This dramatic start was lucky for them and in fact Cortese, who drove uninterruptedly from the start to the finish after an exciting duel with Taruffi-Pellegrina finished second.

There was further excitement with this car. They photograph it in various magazines in smaller races around Italy in 1932 and 1934. Its new best finish was a 1st place in the June 11 Colli Torinesi and the first in class in the Pontedecimo Giovei. Apparently, a pivotal event which encouraged Count Castellbarco to pass the car on occurred on October 10, 1933, at the Monza Grand Prix. We see the car lined up without fenders or lights ready for the start. This great race was also the most tragic in Monza history because an accident which cost the lives of several prominent drivers. Apparently, oil leaked from a Duesenberg bathed parts of the track so unctuous that cars unable to avoid the slick became uncontrollable. Castellbarco’s car overturned and a famous picture of this car belly-up was published in a variety of publications at the time.

That accident cost the lives of great drivers Guiseppe

The next owners were in England where it appeared in various competitions in the hands of driver’s Cyril Hawley and David Brake before coming to the United States to Fred Proctor. After two owners it reached Bill Serri, with whom I had a productive but very stormy relationship. Bill never got around to completing the car, but fortunately left it in its entirely original state. To Bill’s credit, he was one of the first automotive connoisseurs who understood the value of preservation. He appreciated the beauty of original trim, and the credible appearance of original paint on those rare occasions when it was found. Credit for this goes to Bill’s father, a physician and a fine furniture collector who, despite his apparently non-opulent means, acquired some of the greatest American pieces.

Bill needed funds to purchase Alfa 812030, so we also included this Monza in the deal. I did this as a way to get the final funds to Bill so that he could buy the car of his dreams. The complete but unrestored car was sold to Michael DiPaolo, a mutual friend who gave the car to Chris Leydon to restore. By 1988 Chris had already been working on the car to Mr. DiPaolo’s standards which, frankly, differed from mine. But Chris’ meticulous work was very obvious. His attention to detail is uncanny, right down to the proper colored wiring insulation and the minute details which differentiate a Monza from other 8C 2300 Alfas. DiPaolo, however, wanted the car to be perfect. I later owned the car. In one visit to Chris I found the apron between the front dumb irons new, and unpainted. I could not understand the need for making a new piece, and he showed me the original piece on which several louvers were torn and bent.

I instructed him to repair the original piece and put it in place because we had worked hard to keep the original metal. He understood our unconventional preservation criteria. Chris could later save every piece so that the car appeared as it left the factory. His magnificent engine work has stood the test of time. He and I took the incarnadine beauty to Bridgehampton when Bob Rubin owned the track shortly after he finished it, and it has proven to be bulletproof ever since. My only complaint is that DiPaolo’s idea of perfection, which was stated to Chris when DiPaolo was in charge of some restoration, resulted in a level of finish which is far prettier than when the new car was in the hands of Count Castellbarco.