This car is 1 of only 3 built. It raced in the 1921 French Grand Prix at Le Mans and also finished 2nd in the 1922 Indianapolis 500. Dr. Simeone found it unassembled and in pieces at a garage in the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia.

THESE CARS

This pure race car makes its way into our Le Mans exhibit because it is a sister car to the winner of the first post-World War I French Grand Prix they held at Le Mans. This contest paved the way for sports car racing from 1923 until now. The impact of this win on American racing history, as you will learn, is significant.

Building racing cars became the predominant focus of the lives of German immigrants Fred and August Duesenberg from 1912 on. For the 1912 Indianapolis, they entered a 226-cubic inch Mason against the giant engines of larger American and European manufacturers. Still the Mason cars gained attention, which reflected on the Duesenberg. At Brighton Beach, they came in first and second placed followed by four Mercers and two Stutzes! They gave the usual four-cylinder engine up when, finally able to function independently after some corporate changes, the Duesenberg brothers made eight-cylinder engines which would be competitive in the 183 cubic inch formula just officially adopted. The single overhead-cam engine proved both durable and powerful. It entered a variety of races after they announced the 183 cubic inch limit for the 1920 season at the conclusion of the 1919 Indianapolis race.

In 1921, Duesenberg finished in second, fourth, sixth, and eighth at place Indianapolis. The greatest achievement of this model was on July 25 when the Duesenberg brothers sent four 183 cubic-inch cars equipped with four-wheel brakes, a unique feature for any race car at the time, to France to compete in the first post-war French Grand Prix Race on the roads of Le Mans. Three cars were driven by Jimmy Murphy (the overall winner), Joe Boyer, and Albert Guyot. This was one of the proudest achievements in American racing. It was not until the 1960s when an American won an important international race overseas (Phil Hill, Ferrari). And it was not until 1967 when an American driving an American-made car won an international race (Le Mans, 1967, Ford GT 40 Mark IV, Dan Gurney and A. J. Foyt).

OUR CAR

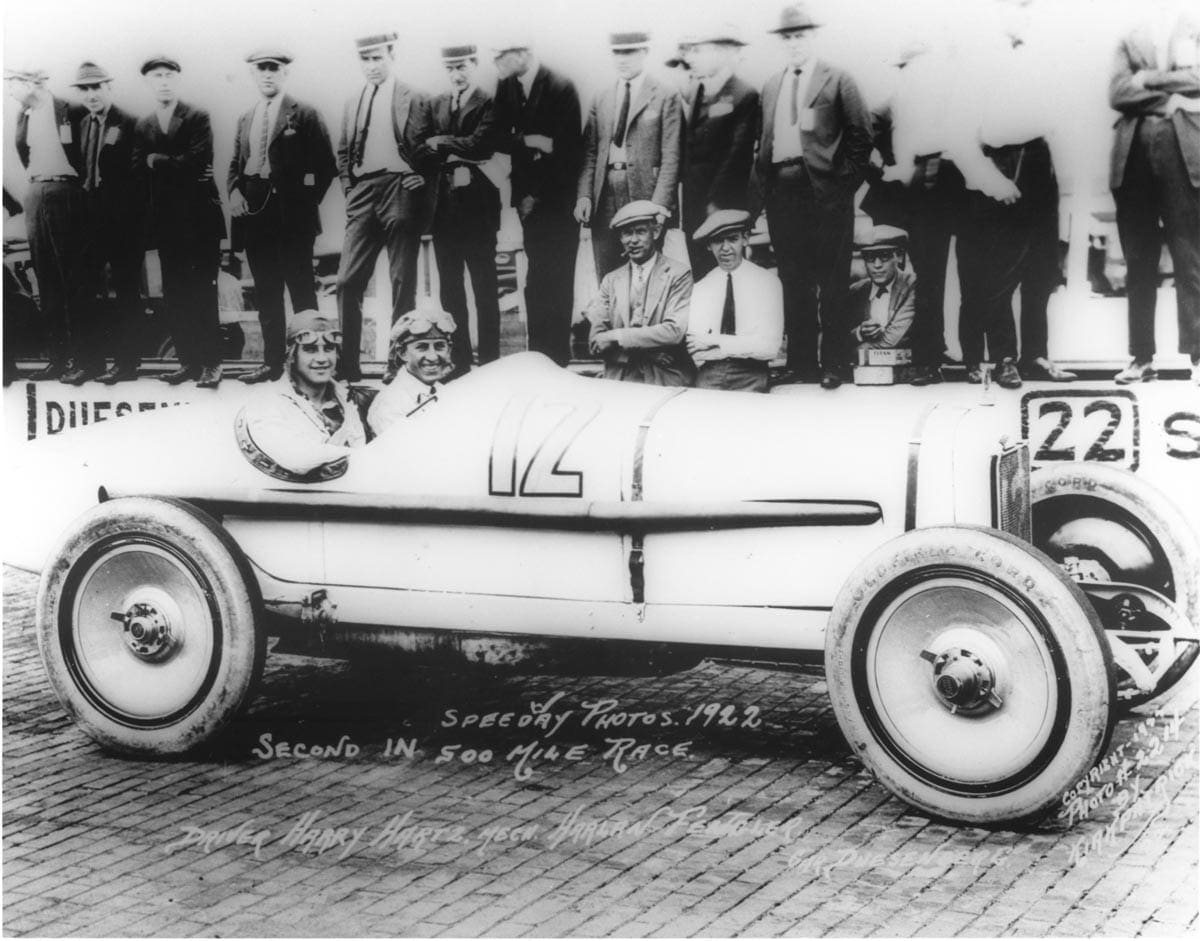

This landmark victory, a singular event in American automotive history for 45 years, was inveighed at the time by the French competitors and their motoring press. Our car, number 16, one of the three cars which raced (the fourth being on the sideline), performed well but succumbed to a thrown piston rod, which occurred on the 18th lap of the 322-mile race, and put the Joe Boyer driven car out of commission. They brought it back to the States and repaired it, and then it sold to Harry Hartz, a dynamic figure in American racing. Harry was from Los Angeles, and his first event was the November 24, 1921, 250-mile at Beverly Hills, where he finished fifth. On December 10 at San Carlos, he came in second place. And in 1922, he came in third in the March 5 Beverly 250. He then changed the number to 12 and entered many major races, his best result being a victory at San Carlos in April 1922. He drove consistently to finish second behind Timmy Milton in the 1922 Indianapolis 500.

Like Tommy Milton and Jimmy Murphy, Hartz knew that the overhead cam Miller engines were now more powerful than the Duesenberg. Yet, the magnificent well-balanced chassis with four-wheel brakes had to be retained, so he installed a new Miller 122 cubic inch engine when the displacement rules changes and upgraded her with a shiny, gracefully pointed, “Miller Nose.” He drove his last race in her on April 26, 1923.

By 1926, the car was on the East Coast, seen in a lineup at the Langhorne racetrack. It was later owned by the Burgert brothers of Philadelphia, who campaigned it on various tracks. In 1931 the Burgerts entered the Indianapolis 500. At that time, the “junk formula” was operative, which meant one could use almost any motor, which in this case was ultimately a semi-stock Duesenberg model A engine with modifications. At Indianapolis for 1931 and ’32, it did not qualify but made the program list, and it remained in the Burgert’s garage in Philadelphia, although it raced periodically until the mid-1930s. Dad bought the car in 1955 along with some spares when it was complete but apart. He never could afford to decipher it, so it had reassembled by Chris Leydon then Fred Hoch for completion. I made it more or less a non-runner since a car like this was not able to run anywhere but a racetrack. One of the outstanding features of the car as we got it, believe it or not, were the original racing Firestone slicks, which were excellent condition, and to this day they have not been reproduced. Although they look beautiful, they are not road capable.

It looked nice in the collection for many years, with its original Miller Nose, original body and chassis, front and rear axles with brakes, gas tank, instruments, and body. We painted the number 43 on it, which was its last AAA racing number when found.

During a friendly visit, Fred Roe, and then Ema, inspected the car carefully, got together along with Joe Freeman, and proved with a series of photos from their collections, and their outstanding knowledge that this was the Joe Boyer car from the French Grand Prix of 1921. I couldn’t believe it and that how this reflects on my lack of knowledge of open-wheel racecars. We then set upon the notion how the car should properly be suited for restoration. It has been my policy that I should leave cars in as-found condition if they were last raced in period. However as-found meant that we would have a car with an impressive race history original except for the engine and transmission, but with no significant modern history in its current form except for failed attempts at Indianapolis (when she was over 10 years old!).

Joe Freeman was eager to have me put the car back to its 1921 Grand Prix glory. And he convinced me it was not very far off, really requiring engine and transmission and some rear body modifications. Randy Ema and Fred Rowe agreed. I talked to Miles Collier about this restoration because he is the guru in terms of understanding and accepting authenticity in the face of conventional thought. He accepted the return to French Grand Prix or “as built” status, the only such compromise we have ever made. We found a proper 183 engine which had been restored at Indianapolis by race engine expert Bill Spoerle. The exact origin of this engine is unknown, but interestingly, it has a repair in the sump when it was “holed” by a blown piston (the reason Boyer did not finish the French Grand Prix). I can’t get much more of a conclusion from that. Joe Freeman was helpful in finding a Brown Lipe transmission, and we brought the whole package over to Fred Hoch in Magnolia, New Jersey. Fred installed the engine, and the transmission bolted directly onto the back of the 183. He removed the Miller nose, preserved it, and then brought back the radiator shell to a proper configuration. The original body is cut short in the back to conform with more modern shapes, probably in the mid-1920s. Lofting curves from several contemporary photographs, Fred reconstructed the back half of the tail and put the whole thing together so that after flat white paint and some lettering, it looks the way it did in 1921.

There is an interesting external feature which has always identified this car. Duesenberg historians described it in the past from photos as the “hand hold” car. Uniquely there is a place cut in the cowl for the mechanic to hold on to, and this appears in every picture of this car from the French Grand Prix to the very latest images. While looking at a copy of an Oliver Hardy movie called “Kid Speed”, I noticed a racing Duesenberg with a Miller nose shot at Beverly Hills, where it was part of the action in a race in which Hardy could win the fair lady’s hand. A few frames from this film show the hand hold car with the Miller nose looking exactly as it did, basically, for the rest of its life, including the Burgert photograph which Dad got when he purchased it. My indebtedness goes to Randy Ema, Joe Freeman, and Fred Roe for making me realize what a treasure we had here.

Sportsmanship, like every other moral quality is not instinctive. It must be acquired. Jimmy Murphy, as no other, possessed the quality of a 100% sportsman. Invariably, when he won, he attributed his success to the goddess of fortune. He carried his honors more blithely than any other man I have ever come in contact with in my 30 years as an official. He accepted victory without a sneer or a strut, and defeat without a whimper. He was one in a million.

Fred J. Wagner,